#30 Cyclomaticly Complex Settings View Controller

Simple screens evolve

In every project simple screens can happen. Let’s think for example of a simple Settings screen. Customer wanted a Settings screen on which a user would be able to Set Option 1 and 2 and to Logout from the application. It seemed so simple so developers used a UITableView with 1 section, hard-coded text displayed in cell and actions invoked directly from tableView(didSelectRowAtIndexPath:).

But it was ok, after all it was just three options, no big deal. When a few weeks passed by, customer came back and decided that the user has to be able to set another two options in the app and that all non-related options should be visually separated. So developers added those options and separated non-related ones by using multiple sections in a UITableView with .grouped style.

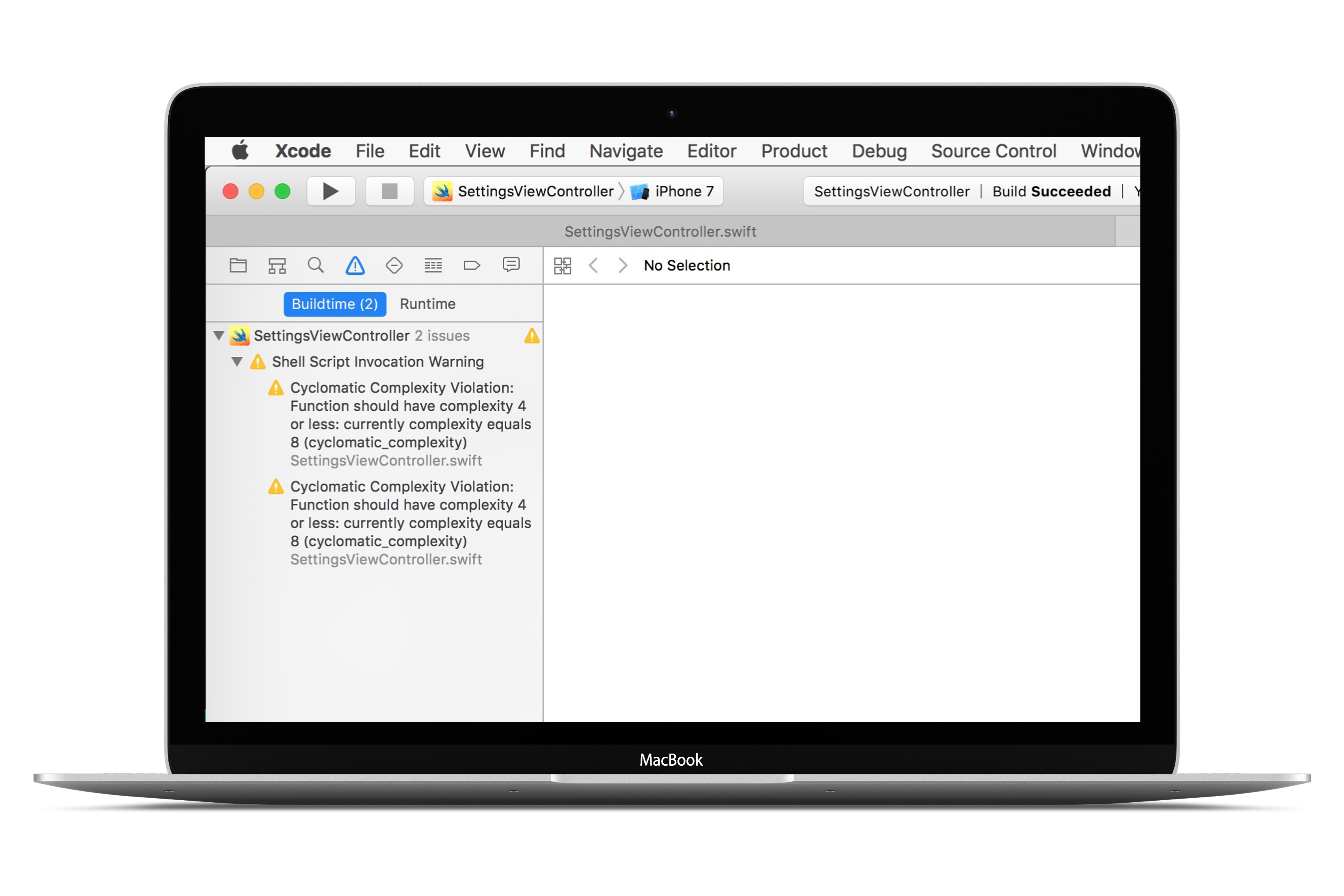

But developers used this long switch statement in many methods that dealt with tableView. They also had been using SwiftLint (a tool for code quality mentioned in issue #11 and issue #26) that indicated that their cyclomatic complexity limits for those methods were overreached.

Wait! Cyclo-what?! 💥

Cyclomatic complexity

Documentation for codebeat (another tool for code quality assurance) mentioned by us in issue #10 has a great explanation of what cyclomatic complexity is:

The cyclomatic complexity of a section of source code is the number of linearly independent paths within it. For instance, if the source code contained no control flow statements (conditionals or decision points), such as if statements, the complexity would be 1, since there is only a single path through the code. If the code had one single-condition if statement, there would be two paths through the code: one where the if statement evaluates to true and another one where it evaluates to false, so complexity would be 2 for a single if statement with a single condition. Two nested single-condition ifs, or one if with two conditions, would produce a cyclomatic complexity of 4. (…)

OK, now when we know what cyclomatic complexity is, we can see some code and resolve its problems!

Cyclomaticly Complex Settings View Controller

So in the end, developers ended up with tableView(:cellForRowAtIndexPath:) method implementation that looked like this:

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, cellForRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> UITableViewCell {

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: cellIdentifier, for: indexPath)

let section = indexPath.section

let row = indexPath.row

switch (section, row) {

case (0, 0):

cell.textLabel?.text = .SetOption1

cell.accessoryType = .disclosureIndicator

case (1, 0):

cell.textLabel?.text = .SetOption2

cell.accessoryType = .disclosureIndicator

case (2, 0):

cell.textLabel?.text = .SetOption3

cell.accessoryType = .disclosureIndicator

case (3, 0):

cell.textLabel?.text = .SetOption4

cell.accessoryType = .disclosureIndicator

case (4, 0):

cell.textLabel?.text = .Logout

case (4, 1):

cell.textLabel?.text = .LogoutAndResetData

case (4, 2):

cell.textLabel?.text = .LogoutAndRemoveAccount

default:

fatalError("Wrong number of sections")

}

return cell

}

Their UITableView had 5 sections, 4 of them contained only 1 row and navigated to a different screen, 1 of them had 3 rows with different option to logout from the app.

The developers had set rigid cyclomatic complexity rule that will invoke a warning when the rule reaches 5 possible paths of execution through the method.

SettingsViewController.swift:58:5: warning: Cyclomatic Complexity Violation: Function should have complexity 4 or less: currently complexity equals 8 (cyclomatic_complexity)

SettingsViewController.swift:90:5: warning: Cyclomatic Complexity Violation: Function should have complexity 4 or less: currently complexity equals 8 (cyclomatic_complexity)

There is also tableView(:didSelectRowAtIndexPath:) method with high complexity. You can check this example project to see full source code.

Cyclomaticly Simple Settings View Controller

OK, but how can we design source code to resolve complexity issues? 🤖

This one simple trick can clean up our code and simplify complex methods. We can use a ViewModel struct to represent cell’s looks and behaviour.

fileprivate struct ViewModel {

let name: String

let indicator: UITableViewCellAccessoryType

let action: () -> Void

}

For the Settings View Controller, the struct contains a name and an accessory indicator to be displayed in a cell. It also stores an action to be performed when user taps the cell. For first row in Settings View Controller we would write such a code:

ViewModel(name: .SetOption1, indicator: .disclosureIndicator, action:

{ [unowned self] in

self.push(SetOption1ViewController())

})

Since method called in action closure is defined in Settings View Controller (self), there is a problem. First of all, a capture list has to be used. Secondly, we cannot construct let viewModel: [[ViewModel]] property before initialization of superclass, because the closure uses self.

To solve that problem, the property can be declared as fileprivate var viewModel: [[ViewModel]] = [] and filled with appropriate data after init of a superclass or in viewDidLoad() method:

fileprivate func setupViewModel() {

viewModel = [

[ViewModel(name: .SetOption1, indicator: .disclosureIndicator,

action: { [unowned self] in self.push(SetOption1ViewController()) })],

[ViewModel(name: .SetOption2, indicator: .disclosureIndicator,

action: { [unowned self] in self.push(SetOption2ViewController()) })],

[ViewModel(name: .SetOption3, indicator: .disclosureIndicator,

action: { [unowned self] in self.push(SetOption3ViewController()) })],

[ViewModel(name: .SetOption4, indicator: .disclosureIndicator,

action: { [unowned self] in self.push(SetOption4ViewController()) })],

[ViewModel(name: .Logout, indicator: .none,

action: { [unowned self] in self.showLogoutPrompt() }),

ViewModel(name: .LogoutAndResetData, indicator: .none,

action: { [unowned self] in self.showLogoutAndResetDataPrompt() }),

ViewModel(name: .LogoutAndRemoveAccount, indicator: .none,

action: { [unowned self] in self.showLogoutAndRemoveAccountPrompt() })],

]

}

Now implementation of tableView(:cellForRowAtIndexPath:) is as simple as that:

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, cellForRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> UITableViewCell {

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: cellIdentifier, for: indexPath)

let section = indexPath.section

let row = indexPath.row

guard let model = viewModel[safe: section]?[safe: row] else { return cell }

cell.textLabel?.text = model.name

cell.accessoryType = model.indicator

return cell

}

You can find full sample project here.

TL;DR;

Simple screens with naive implementation can grow fast through time and turn into complexity burden. It’s good to have a code quality guard to warn you by saying Fix it!. If you don’t have a clue how to fix an issue, ask your colleagues, switch your thinking from switch statement to some abstraction, watch Swift Talks and read blog posts to be more creative in problem solving!